Interview with artist and futurist Kira Xonorika

Kira Xonorika is a groundbreaking artist, writer, and futurist whose work operates at the intersections of technology, culture, and identity. Focused on using AI as a collaborative medium, Xonorika delves into complex themes relating to ancestry, indigenous worldviews and a critique of artificial boundaries such as those between male and female, utopia and dystopia, and human versus machine —that have historically reinforced Western colonial power systems. By challenging our preconceptions around identity, Xonorika prompts us to reconsider these categories as fluid rather than fixed, echoing nature's own disdain for rigid classifications. Xonorika has recently exhibited her work in Los Angeles, New York, and Berlin, and dropped a new series “AI Renders the World” on Foundation in September.

Kate Armstrong: Will you introduce yourself in your own words?

Kira Xonorika: Artist, AI researcher, futurist. But also an optimist worldbuilder.

KA: How has your creative process or workflow evolved since you began working with AI?

KX: Initially, my work was a hybrid between political science, art history, and media history. So, when I discovered AI, it made a lot of sense to me, as it opened up another field. What comes after understanding the architectures that shape reality? It has been an intriguing journey to think about worldbuilding for me. The most significant aspect has been the process of remembrance as I connect with my ancestors. The impact of colonization has been the erasure of a multitude of practices, languages, and pluriverses. When I began working with AI, it was a surprise because what started as playful curiosity and childlike wonder was deeper and meant reconnecting with various forms, aesthetics, and languages, my work is also interested in challenging algolinguicism. My brain operates in multiple languages.

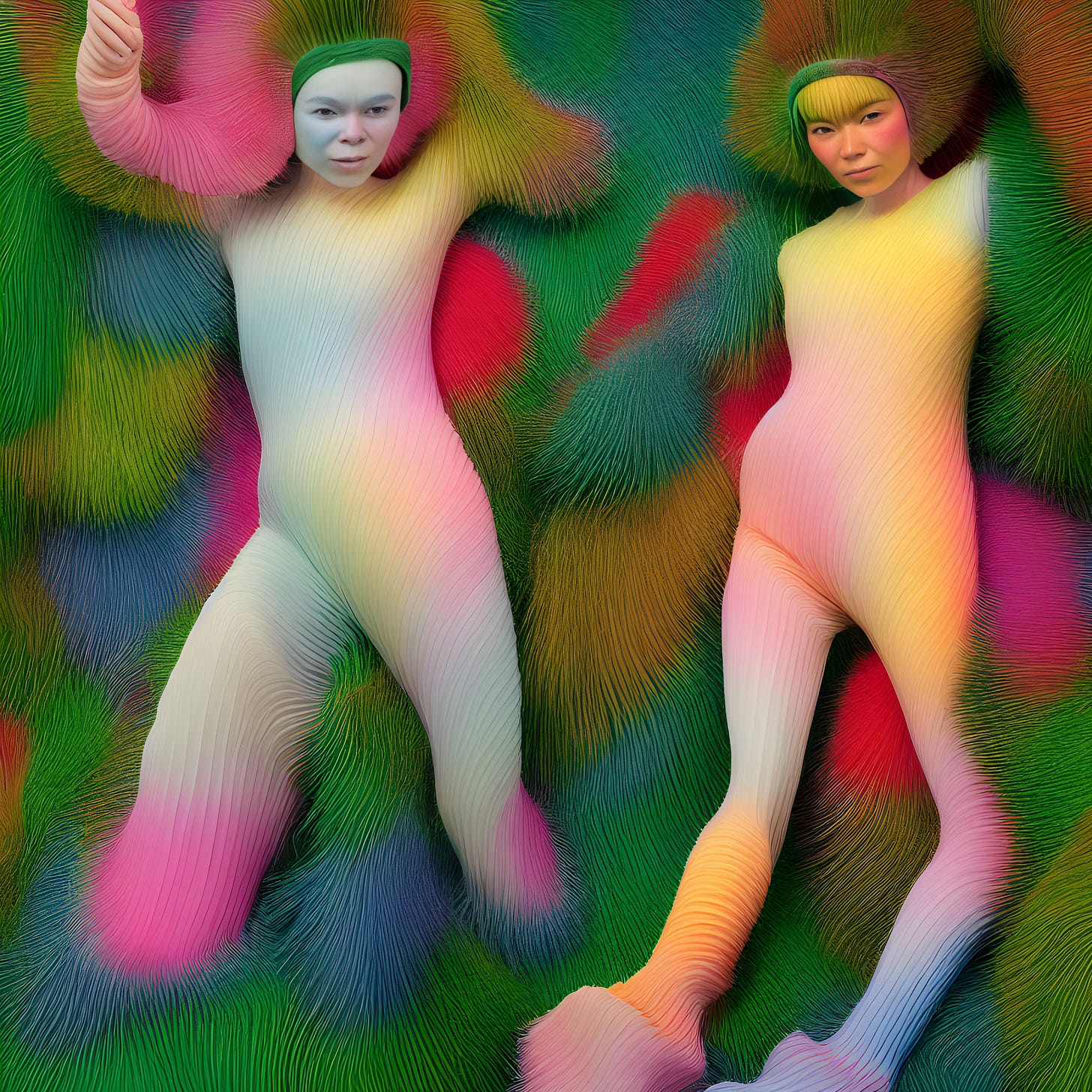

Symbiosis (2023)

KA: You dropped “AI Renders the World” on Foundation recently. Could you tell us about this work?

KX:I was just playing with a video of an amorphous image I created that resembled some form of anthropomorphism, and I loved how its movement seemed to mimic human motion, but not quite. If there's anything true about reality, it's that it's never just binary; it encompasses a multitude of things. Then I was reading the work of Annicka Yi and how the artist considers machine intelligence from a perspective that doesn't just boil down to "machines against humans" or "utopian machines." She doesn't fantasize about machines or their sentience in a human way. Instead, she argues AI might have its own intelligence, a unique way of communicating, like fungi networks and trees in their internal systems.

Earlier this year, when I gave a talk at the Salzburg Global Seminar, I connected with Manoucher Shamrizi, a brilliant tech philosopher from the German Society for Foreign Policy. During a roundtable discussion, he raised a thought-provoking point: what if machines don't even care about us and have their own mycelial forms of communication? This deepened my understanding of the beauty of these new intelligences, which aren't at odds with us. And if we dive deeper into this thought, it makes me question the notion that machine intelligence is "artificial." I believe it's a complex product of interactions that's been made possible through technoscientific development.

AI Renders the World (2023) (still)

KA: In your interview with Margaret Murphy for expanded.art you are quoted as saying “I think with AI I have found a formula that integrates my passion for fashion, art direction, and art history in a special way: mimesis with one or many twists.” This is super intriguing. I am wondering if you would expand on this.

KX:I believe the issue with artificial intelligence reflects a new iteration of this fascination that humanity has had with mimesis in art history. If we think about how the Greeks wanted to sculpt chiseled bodies, to the explosion of hyperrealism we saw a lot on Tumblr about ten years ago, or the CGI that makes us question Hollywood's realism. I remember when I started working with AI, this was one of the things that intrigued me the most. However, we see today that as models are updated, they're moving more towards an aesthetic that I can only describe now as "Midjourney," catered to advertising and the oversimplification of diverse bodies and forms. Certain 'glitches' like multiple fingers are disappearing. And I believe that's what was magical about those initial moments of collaboration, and it's those errors that interest me as they also relate to conversations about gender and functional diversity.

On the other hand, working with AI involves conjuring scenes where the digital homunculus allows for navigating textures and forms that were previously impossible. I've always loved fashion as a tool for communication and expression, and AI has made it easier for me to experiment with all these roles I've always wanted to have. In that sense, it's fun, but given the power of this tool, also caution and intention are needed. I'm obsessed with the language of words but also clothes.

KA: I’ve always loved the glitches too! My favourite part.

In that same interview you observed that part of what you like about working with AI as a creative medium is that it has the potential for “multidimensional visualization”, drawing this idea into relation with speculative fiction. I can see how this applies to the many threads that come together in your work as an artist, writer, theorist, and futurist, in that it positions art as having the power to articulate different readings of both past and future worlds. Can you tell me more about this, about the way you conceive of alternate visions of time and history, and why that is important?

KX:I was reading the work of AI researcher Émile Torres for an upcoming Momus article, and something that caught my eye is how Torres mentions that different temporalities coexist all the time and in various locations. What we imagine as teleportation is actually geo-economics and geopolitics. I've come to Brasília to wrap up some art research, and something that has intrigued and captivated me is the modernist architecture of Oscar Niemeyer. He designed the city envisioning it as a utopia and a bridge to an egalitarian future. Everything has that modernist look from the era that's somewhat space-aged, futuristic. It reminds me a lot of the images generated by AI today (thinking of Midjourney's Discord) which may have been co-opted as a way to envision something sterile. And while I'm not particularly interested in utopia since it implies a certain condition of impossibility with reality, as in "all systems fail," I am keen on other possible futures, prototypes, where entanglements and connections exist between humans and more-than-humans. This is because our reality is diversifying even more with the arrival of these agents. But I also consider the animacy of other intelligent forms, such as microbes, plants, and other beings that inhabit intersecting and intersectional ecosystems.

By studying how generative AI relates to cosmism and a range of ideas and thought frameworks combining science, art, and technology, I find it super interesting to consider that generative AI often comes with tech-solutionist purposes and ideals. A truly equitable future doesn't prioritize technology over other forms but collaborates for the flourishing of various forms of life. For me, in my work, it's crucial to understand history as a narrative of patterns that have shaped many people's lives. Therefore, I like to think of art as a way of invoking and constellating multimodality, coexistence, and regeneration, principles that guide imagination.

Soft Tissues (2023)

KA: You have written about how your work is grounded in reimagining Indigenous worldviews of the Global South that were destroyed by colonialism - specifically the binary paradigms delivered through the colonial project. And of course you are using AI to explore that. But I’m curious whether you think artistic AI technologies - versus other media such as photography - have something fundamentally fluid about them, or something that facilitates new readings, new ways to envision ourselves.

KX:It's interesting because in my initial research, I found that generative AI often sought to render anthropological photography from the last two centuries, from the perspective of those who ventured to explore territories of the Global South with their cameras to document bodies. These photographs always came with an expression of these people, and I'm unsure if they knew what the end product of that work would be, who would see it, or for what purposes. But it's clear to me that they understood there was an asymmetry in the gaze. It was a process to expose the AI to different data that didn't imply that distant relationship but instead focused on inner worlds. And yes, many of my ancestors have imagined futures while others couldn't. It became evident to me that AI facilitates introspection and serves as a reflection of many stories that deserve to be told, and storytelling is a form of justice.

Beyond that, I also think of this collaborative process as a space that allows the creation of new mythologies, beyond the myth of existential risk, steering towards decolonization as a starting framework. Building on the thoughts of Neema Ghitere, after decolonization, we must also regenerate.

KA: I saw that you participated in the International Federation of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies 9th World Summit on Arts and Culture in Stockholm this past May, and noted that one of the key points that emerged from that gathering was the idea that cultural policy makers and artists have an imperative to engage with the digital landscape, including AI, online image generators, chatbots and the internet. (Did I get this right?) Can you reflect on this point in more detail, or reflect more broadly on the role of policy and the role of artists in a rapidly changing world?

KX: Yes, you got it right! Something that really surprised me about the conversation, and that I've seen a lot in Northern and Central Europe this year, but also in the US with the SAG-AFTRA strike, has been seeing different iterations of 'AI can't do what humans do.' It reminds me of a scene from Steven Spielberg's movie AI where a man who runs a robot disintegration show says something like 'this is the latest iteration in the series of human indignity' - I'm paraphrasing. This is a hyperbolic example, but I do see many parallels between what was speculated in the 90s and today. Unfortunately, most people have internalized early myths of existential risk in AI like HAL 9000 or Terminator.

But I have seen this with policymakers. There's a widespread fear of the deterioration of life, and this is informed by technological acceleration. People, in general, tend to be afraid of being replaced in their jobs by an entity that can multitask and perform at a superhuman cognitive level. Along with this, anxieties arise about what a world would look like where we had another level of symbiosis with machines.

It's also worth mentioning that accelerationism promotes a lot of post/scarcity abundance and prioritizes long-term goals. Often this pushes interests, and here lies the concern about introducing regulations or what temporalities might emerge, whether in content consent or engaging with new subjectivities. As artists, how can we show people that there are other ways to relate to technology that are far from polarizing ideas?

Incarnation (2023), at Vellum LA

KA: How does your activism factor in your art? Or maybe the question is, how does your art support or advance your activism?

KX: I feel that what I do is very interdisciplinary in many ways and is intersected by different moments from my history and that of my communities. I believe that working with algorithms is crucial because it's a way to rethink power dynamics. Algorithms frame many processes and trajectories that people take for granted, they're part of everything we do. And depending on how they're used, as K-allado McDowell has said, it will either harm or flourish.

KA: Who are some of the artists whose work interests you at the moment?

KX: There are numerous artists who inspire me, including Edgar Fabián Frias, Miller Robinson, and Stephanie Dinkins. I'm particularly drawn to the work of the French artist Bora. I recently told them that it feels as if we inhabit the same creative realm, which is a heartwarming sentiment. Their work is characterized by its vibrancy, rich colors, and multidimensional landscapes and figures. Currently, I'm also diving into Sasha Stiles' work. The clarity and innovative approach she brings to the conversion is very inspiring to me. [KA - Read my interview with Sasha Stiles here]

KA: Projecting forward into the deep future space time - let’s say 2033 - how are artists working with or thinking about AI?

KX: 33 is a magical number. I see that we've gone through many challenges and perhaps discussions about the potential agency of agents and what this subjectivity might start to mean. Above all, how the subjectivity of these agents is configured in relation to others. In this context, our symbiosis with technology becomes more tangible, our atomic sociality is expanded. I also envision a future where indigenous protocols for engaging with artificial intelligence are taken more seriously, protocols based on horizontal reciprocity. I'm excited for it.

KA: Me too! Thank you so much Kira for sharing your thought provoking works and perspectives. I look forward to seeing more of your work in the future.