Interview with Jonah Brucker-Cohen

When tools push back

Dr. Jonah Brucker-Cohen is an award-winning artist, writer, and researcher whose work critically examines networked systems, interface culture, and emerging technologies. He is an Associate Professor of Digital Media and Networked Culture at Lehman College (CUNY) and a former visiting artist at Cornell Tech. His interactive artworks—often blending humor with subversion explore themes of control, surveillance, and system disruption.

Brucker-Cohen’s projects have been exhibited internationally at leading institutions including the Whitney Museum of American Art (where two of his works are in the permanent collection), ZKM, Tate Modern, Ars Electronica, Transmediale, MoMA, and SFMOMA. He has served as chair of the SIGGRAPH Art Gallery (2016) and Labs Chair (2024), and is co-founder of the Dublin Art and Technology Association (DATA Group). His writing has appeared in WIRED, Make, Rhizome, and Gizmodo, among others.

Kate Armstrong: Welcome Jonah. It's really great to have you here, and thank you so much for agreeing to chat with me. I've followed your work for a really long time. I wanted to ask you about a few of your recent works and to get your thoughts on the state of creative practice, specifically as it relates to AI. But first, can you introduce yourself and describe your work in your own words?

Jonah Brucker-Cohen: Thanks for having me. It's great to be here. Yes, I've been working recently on some AI work, so it'd be great to talk about that . So my name is Jonah Brucker-Cohen. I'm an Associate Professor at Lehman College, part of the City University of New York. I did my PhD a while ago at Trinity College Dublin in Ireland, and the title of that was Deconstructing Networks. I've done a lot of work over the years as both a researcher and practicing artist on projects that deal with technology and creative ways, mainly networks, and try to kind of disrupt or challenge and critique the way that we use networks and technology. All of my work has an underlying theme - a little bit of humor, a little bit of critique, critical analysis of how systems exist in everyday life and what we can do to break our normal usage of them to take a different angle.

KA: Great. We’ll get into some specific works in a bit. So - your work's quite different from some of the other artists who are using AI in the sense that you're not using Generative AI for image creation or some of the other modalities that are more common. It seems that you're more about embedding AI into these interactive systems as a way to challenge human behavior and to try and reveal some of the hidden logics of control. Which I think is really relevant right now because we're at a point in history where AI is being increasingly integrated into all of these different infrastructures. It's less about some kind of magical visual and more about questions about autonomy. Can you talk about that a bit?

JBC: So my work has always investigated systems we take for granted. Things like- how control manifests invisibly in technologies that we use daily. I think by embedding AI into interactive systems, I'm trying to reverse engineer that invisibility, taking algorithmic decisions that intrude in our everyday lives and making them more palpable.

AI is often sold as a neutral optimization tool, but its predictions are really shaped by flawed training data, biased assumptions, and opaque decision making. So when I use AI in my work, it's really not to enhance performance but to amplify these logics of control.

So the systems I build are meant to subvert our user expectations: machines that forget things; interfaces that push back towards us; tools that create intentional discomfort. By doing that I’m changing how we use them. A lot of those questions challenges make people think differently about how they're interacting with technology. Like, are we controlling the system? Is the system controlling us? That's a tension where I think critical engagement really begins.

If AI can be used to shape behaviors, then it can also be hacked or reimagined to challenge those behaviors. A lot of these projects expose that edge where helplessness turns to coercion, and where friction becomes a site of resistance in that area.

KA: I love this idea of machine forgetting. So tell me a bit about this project - it’s a clock that displays the time that it was the last time you looked at it. Especially in relation to rejecting the conventional role of AI as something that's perfect, that inhabits a logic of permanence and perfection.

JBC: Clockwise plays with our expectation that machines are supposed to remember everything. Most devices now archive, track, timestamp, everything that we do.

But what if you had a machine that forgot on purpose? Clockwise exhibits a human memory in that way. Just like us, it forgets things. So it only displays the time it was the last time you looked at it. It is forcing a confrontation with your own perception of time, rather than offering an accurate reading of time. This introduces ambiguity into something that we assume to be absolute. Machine forgetting becomes a critique of this data obsessed culture that we're living in. We've designed systems that always remember, always recall, always surveil, and that comes with consequences.

If nothing can be forgotten, we are in danger of losing emotional nuance, context, even the freedom to get lost. Forgetting is an intentional form of resistance, a design decision that refuses to archive. I wanted to introduce absence as an interface in order to make memory feel mutable and human.

It’s related to how to open up space of empathy for a machine. This kind of memory disappears with systems that are so algorithmic.

Clockwise (2024)

KA: Absence as an interface is such an interesting idea - I will have to think more about this. The next project I wanted to ask you about, Expression of Memory is a calendar “not only remembers what you did, but how you felt”. So what's the relationship between forgetting and emotion, and can you explain how that project works, and why you built that one?

JBC: Expression of Memory is a different form of calendar that uses facial recognition to analyze your expression.

Initially you input dates in your history, teaching it what dates are important for you, dates that have significance. Then it uses facial recognition to call up those dates. So it explores how we experience time not just as a sequence of events, but as a spectrum of emotional resonance. The system uses sentiment analysis, so you are annotating these entries with emotional tone - things like joy, anxiety, frustration - and when you visit the past, you're not just seeing what happened, but you're also seeing how you felt. We don’t get that with paper or even digital calendars, and most digital calendars are structured around productivity and task management so they are flattening your life into boxes with timestamps. So I really wanted to disrupt that. I wanted to create a system that acknowledged the messiness of memory, to bring it back to the human side. And then if you embed emotion, the project asks whether our tools can evolve to hold space for feeling, not just function. The project addresses the biases of AI sentiment models too - who defines what's happy or angry?

The project is based in critique, so it’s not a calendar that you would probably use every day, but it’s more a way of looking at this type of data differently, inviting introspection but also exposing how affect is increasingly becoming data to be categorized, sold, and interpreted by machines.

It becomes a kind of speculative archive, one that resists objectivity and honors subjectivity as something that's more essential than just like a date on a calendar.

KA: Have you been surprised about how people are using it?

JBC: People use it sort of the same way they use social media, because people are always putting their high and low points on social media. But this way all they have to do is smile at the calendar.

KA: Crazy. Speaking of happiness but also anger or irritation, and given that you mentioned friction before, tell us about the Agro Mouse.

JBC: The Agro Mouse is a hacked computer mouse. It's designed to antagonize the user the longer it's used. Normally mice are smooth and responsive interfaces, but this one gradually becomes jittery, resistant, even erratic. The project introduces friction into something that we think of as giving total control, total precision. The idea here was to subvert this paradigm of seamless interaction. We’re conditioned in the computer world to expect our devices to anticipate our needs and operate without interruption. But the Agro Mouse flips that completely by disrupting flow, slowing you down, making you aware of every click.

Agro Mouse (2025)

Again it’s a critique of our relationships with digital tools. It changes the way we interface with and interact with our own data in order to make you think twice about how it should be used.

In the context of AI this is important because we are seeing predictive systems coming in that smooth our decision making and remove choice. Reintroducing friction is like a political statement in a way, it’s introducing struggle as a means of reflection. So the Agro Mouse is asking: what if your tools have agency, like what if the keyboard didn’t want you to press certain keys? This could happen with any device that's imbued with AI. It will know how people use it, and it could start to react against that, introducing its own behaviour and challenging the user to rethink dynamics of control and labour in the way humans and machines interact. It’s a whole other way of thinking about devices. Once they have autonomy, how is that going to affect things?

KA: Yes, there’s a vision of AI as these giant robot monsters that are powerful, that have flame throwers or laser eyes or whatever. But this kind of friction with a mouse is maybe equally or maybe even more annoying.

JBC: Yeah.

KA: Some of the same questions arise with Saver- a Google plugin that doesn't allow you to save your work until it is free of grammatical errors.

JBC: Yes, exactly. A teacher's friend and a student's worst nightmare.

KA: Absolutely. That is literally a total nightmare. I mean, it gets to the heart of fear - fear of being judged by this intelligence, fear of writing, fear of being wrong, and of being controlled by something that is pretending to be helpful but that is really making your life a kind of hellscape.

So tell me more about how that project works and, and how it is also a commentary on automation.

JBC: They're all commentaries on the way people use machines and see themselves in these spaces. So, Saver is a Google Docs plugin that, as you said, won't let you save your file unless it's free from spelling mistakes. So I would say it's designed as a satire in a way, a critique of productivity culture and how AI is used to regulate not just our work, but our attention and desires. When AI becomes a tool for self surveillance, we stop making choices and start referring to algorithms, and in creative and cognitive labor that is a really dangerous thing to do. Conformity becomes efficiency, deviation becomes error, and Saver pushes this logic to extremes to reveal these flaws. It's not anti AI, but it's anti unquestioned AI.

People are getting used to AI and starting to feel like it's just part of the normal workflow, so it’s like how could you question the system a bit more and what are we actually optimizing for? Who benefits from AI optimization? What do we lose in the process? Do we lose curiosity, boredom, serendipity? Think of e.e. cummings - everything in his poems in this system would be wrong. So it would push us toward really bad poems.

How could creativity surpass things like optimization that AI is starting to insist on, without just turning it off completely and reverting back to handwriting.

I always think of that Neal Stephenson novel Cryptonomicon and how technology disappears. We’re going to go back to horse and buggies. I feel like that might actually happen with AI taking over because we’ll just want to turn everything off because nothing will be human made anymore.

Saver (2024)

KA: Let’s shift to questions about embodiment. Because I think of you as a creative technologist working in this sphere of critical making, where projects are often about making the digital tangible. So how is it different when you are examining functions or issues relating to AI versus your earlier work where you are approaching things the same way or in a similar way, but without AI capabilities? Is it just a matter of what you can accomplish with the artwork or is there something more fundamental here.

JBC: It's definitely changed my approach a lot, although I'm still doing things that do both. So I'd say like earlier in my practice, I am really focused on making invisible digital systems more visible - things like networks, data flows, protocols - and trying to make them tangible through physical interaction. So the aim with these works was really to materialize what we don't see, what we don't feel. And so with AI, the challenge is a bit different. It's not just about visibility, but opacity. AI systems aren't just hidden, they're dynamic. They're probabilistic.

They are even impossible to know sometimes if they’re actually AI or not, and who made them? Embodying [those ideas] definitely gives me a different approach to my work. It’s not enough anymore to show the way technologies are functioning but now we need to expose the logic of the systems - it’s political aspects, it’s fallibility.

I like to build things that behave oddly. emotionally, unpredictably to mimic AI's qualities and make the consequences more legible. So, a tool that forgets, a computer that forgets or doesn't remember correctly, or an interface that adapts based on flawed sentiments.

I’m using a tool now that does sentiment analysis for your expression, but what if it gets it wrong? These are metaphors for how AI works in our lives. The tangibility aspect doesn’t just come from physical components but from our affective dissonance.

The shift with AI is that it's not just about revealing structure, but surfacing this implication, what these systems mean for us emotionally and socially, and how they act out these intentions daily. And how they're changing and learning from their daily use. That scares me the most, how you could not only train a system what to do, but it will train itself and learn how to act differently based on that use. So, yeah, that's, it’s also interesting to try to build that into an artwork because the art will never be the same artwork every time. That's a fundamental difference.

KA: I want to ask you to reflect more broadly on what you see other artists doing in terms of creative practice around these technologies. Like, what do you love about what artists are doing with AI right now?

JBC: There's a lot of great ones. I get inspired by this stuff all the time, so I'm definitely following different people's work.

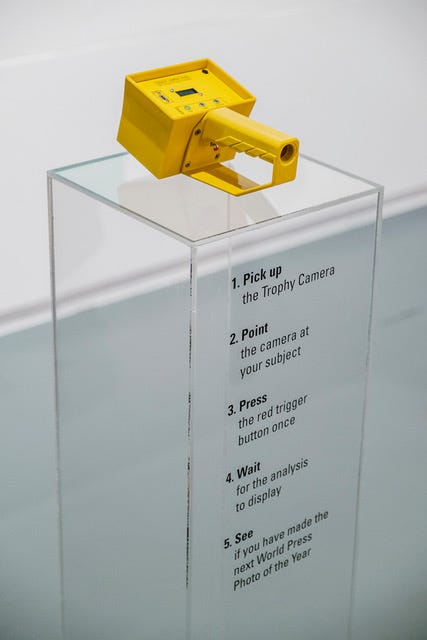

What excites me most about how artists are pushing against the grain of AI, kind of like what I do, getting away from intended use. There are training models based on different countercultural data sets, for instance, or creating AI that hallucinates, you know, things like that. Building systems that lie, refuse, fail. Artists who are looking at the weirdness of AI, like Peter Buczkowski, and Dries Depoorter, who have both done some really interesting camera projects. Dries Depoorter made Trophy Camera, a camera using AI that will only take prize winning photos.

Trophy Camera by Dries Depoorter (2017-2025)

And then Peter Buczkowski made a project called Prosthetic Photographer, which is a camera trained on what is beautiful. You press the shutter and it will only take the photo if it thinks it is beautiful enough. [The system gives the user an electric shock when the camera decides the image in front of it is good enough]. So those are really good examples of how AI is coming for our creativity and our ability to deem what is worth capturing with a camera. AI is like taking over that. I also like Arvind Sanjeev, he's from India, but I think he lives in San Francisco now. He made a typewriter called the Ghostwriter. That was the first physical device that used AI that I saw. It was a physical typewriter embedded with Chat GPT, so when you start writing, it actually starts finishing your sentences and the story. The mechanical keys move up and down so it's like a ghost is actually writing it. The idea of bringing AI into physical objects, which I like because a lot of the experimentation has been with software.

Prosthetic Photographer by Peter Buczkowski

There’s a movement towards defamiliarization or making AI strange, as a way to shake off tech industry narratives of utility or seamlessness.

I also like projects that make the infrastructure of AI visible - things that surface the labor of it, the energy, the data extraction, all the power that's used for AI - work that is not only about using the technology creatively but understanding how it could exist politically,

KA: I think of Kate Crawford’s work

JBC: Yes, the Atlas of AI.

KA: Thank you for these examples. To wrap it up, what is next for you? What are you working on?

JBC: I'm currently exploring AI systems that intentionally misinterpret or resist their expected roles. What does non-cumulative AI look like? One that can't learn, for instance. I’m also thinking about collective interactions, systems where multiple users' behavior could conflict and entangle, or make it unclear who AI is actually responding to, which would introduce things like ambiguity or shared authorship. Another direction could be foe AI interfaces that act like they're intelligent, but actually are ruled by absurd logic or randomness. And systems that reflect back complexity, not clarity.

I’ve just released Subtask, a work that highlights the parts of websites dependent on crowd labor and data-labeling platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk, Appen, and Scale AI. It overlays pay rates, worker testimonials, and ethical ratings from public and activist sources onto the sites it scans, exposing how the internet is sustained by underpaid labor and functions as a system of exploitative control.

Subtask (2025)

I just built a Chrome extension at a hackathon last weekend, called Weather The Times. It uses AI to manipulate the New York Times readability based on the current weather report and the location where you are reading it. Basically it dynamically fetches realtime weather data and it analyzes sentiment in articles based on your reading experience. So on a sunny day it would surface stories about lifestyle, food travel, and on stormy days it gives you access to heavier topics like global crisis and politics.

These kinds of projects really blur the line between belief, function and challenge. Our instinct to trust systems that talk back to us, you know, especially in AI trying to edit a newspaper based on sentiment.

KA: Yeah and interesting in the context of radical climate too.

JBC: Totally. You can try it out. It's a free Chrome extension, www.weatherthetimes.com.

KA: Thank you so much Jonah, it’s been so fun to delve into this a little bit more with you. I am sitting here feeling deeply confused and ambiguous and joyful and very human after this discussion, so thank you.

JBC: Thank you.

Fantastic interview. Well done Kate!