Interview with Ross Goodwin

New forms of writing using machine learning, AND he wrote a novel by driving a car across the United States using the car as a pen

I had the chance to chat with Ross Goodwin, an artist whose work I’ve loved for a really long time.

Ross employs machine learning, natural language processing, and other computational tools to realize new forms and interfaces for written language. From word.camera, a camera that expressively narrates its photographs in real time using artificial neural networks, to SUNSPRING (with Oscar Sharp, starring Thomas Middleditch), the world’s first film created from an AI-written screenplay; from making London’s Trafalgar Square lions roar poetry (“Please Feed The Lions” with Es Devlin), to writing a novel with a car (1 the Road), Goodwin’s projects and collaborations have earned international acclaim.

Kate Armstrong: So - thank you so much for participating in this interview, Ross. It's great to see you again. And I've loved your work for such a long time. It's really exciting for me to have a chance to delve into it with you, so thank you.

Ross Goodwin: Oh, well, thanks for having me. It's really wonderful to be here talking with you. And yeah, it's great to see you again. And I really appreciate the kind words about my work.

KA: Nice. So you've been described as an artist, creative technologist, hacker, gonzo data scientist, poet, writer, and I cannot help but mention that you were also a ghostwriter for the Obama administration. Which I think by the way is the craziest bio that I've ever heard. But before I get into questions, I'd like to ask if you would describe yourself in your own words.

RG: Sure. I just like experimentation, and my interest, when I learned to code, gravitated toward the intersection of writing and computation. So that's where my interests [still] lie, and the landscape has continued to evolve over the years since I began. This journey of working with text and computers has changed dramatically in the last couple of years, in fact.

KA: And so what are those changes like? How would you describe that?

RG: When I started working with Markov chains and context free grammars in 2013, 2012, 10 years ago, artificial neural networks weren't really a thing. The state of the art for generating text was very choppy. It didn't look human and nobody really thought that computers would be able to write at a human level for quite a long time. That was seen as a very distant goal.

But then the whole idea of deep learning artificial neural networks really came into vogue and started working well due to [the] advances in statistics and hardware that have happened over the course of the last 10 years. So when I started working with these technologies or just with language and computation [in general], it was a very different world. The hot code toolkit to use was NLTK, which still exists the natural language toolkit. I think the field was probably thought of as natural language processing - people still use that term - but it means something different now due to the advent of artificial neural networks. [...]

But the idea of translating data into a paragraph of human readable text, that was the starting point for me.

KA: There will be some people who aren't familiar per se with large language models and how you work with them or how they function in an art practice. Would you mind just describing how you are approaching writing and artmaking when you're working with a large language model?

RG: Sure. I think it's even better to start with language models, you know, rather than just going to large language models, because [even] a Markov chain is a language model. It's just not nearly as sophisticated as GPT4 or a LLaMA or any of the state of the art large language models that exist now. But Markov chains and simpler language models do have advantages in that they run quite a lot faster. They're quite a bit less computationally expensive and they can still do interesting things.

But fundamentally a language model is a predictive text system [that has been] given a corpus of text, or a body of text. Corpus means body in Latin. It's trained on a corpus, meaning that it reads that corpus over and over again computationally, or just once in the case of a Markov chain, and given a sequence of letters, spaces and punctuation, it’s able to predict the next letter, text character, or word, as the case may be. And I found that language models have a place in a number of types of projects. There's a lot of ways they can be used. When I started working with convolutional neural networks or image- concept extraction systems in 2015, I think people saw it as being an image captioning system, but there's so many richer possibilities for systems like that.

We're talking about a system that can understand language at a fundamental level using different facets than what humans use to understand language. A language model has no concept of a noun or a verb. It just knows what the probability distribution of different sequences of letters, spaces, and punctuation have to do with each other. So that's the level at which it's engaging with language. And we found that they work really well now due to a number of advances in statistics over the last few years. Maybe I'm getting further away from the question.

KA: Not at all. Because I think that probably leads into the word.camera project, right? I wanted to ask you a bit about that because the word.camera pops up in a number of your projects. At least I feel like that’s the case - maybe you can correct me if I’m wrong.

RG: It definitely has. I've iterated on it like 10 times over the years, at least.

So it's, it's been a number of versions of it.

KA: So that's an image to text device, right? Can you tell us about that?

RG: Sure. It's worked in different ways over the years. But the systems can be described the same way, which is that there's always been like two artificial neural network systems at play. One which extracts concepts from the image as a set of words related to entities that it finds in the image. And then another one that expands that set of entities into a poem or an expressive text based on the image in real time. The real time aspect has always been really important to me with this project. I want it to be like a camera or a Polaroid, where you take a picture and it prints out text on a receipt in real time. And I guess the whole idea is about redefining the photographic experience. Can we write with implements like cameras, you know? Can we treat a camera like a pen? Could you write a novel by taking a series of photos? Those are profoundly interesting questions to me.

I've used different neural networks over the years and different algorithms. The state of the art is called a transformer-based neural network. But I think we get lost in the vocabulary of all this technical stuff and really what we're talking about here is expressive image captioning or expressive generativity from an image and [whether that] can inspire us in different ways. Can it help us redefine the photographic experience? I think those are interesting questions.

KA: I was going to ask you about 1 The Road. In this project the car becomes the pen, right? So you're driving a car from New York to New Orleans, and this car becomes a writing machine that [creates an] AI version of the great American literary road trip.

RG: Yeah. You got the elevator pitch. Exactly. Right.

1 the Road by Ross Goodwin

KA: How did you get into that as a project, how did that project form and what inspired that?

RG: [That] project spun straight out of my thesis at NYU ITP, which was called Narrated Reality. Initially [it] was one device that narrated image, location, and time, in a backpack that I wore around New York City. The backpack had a camera on it, and a GPS unit, and a clock, and a computer that would print out a receipt [with text]. [When] talking to Taeyoon Choi, who's a great academic in New York and just a wonderful person in the computational creativity community, he suggested [that] I split it into three devices - one for image, one for location, and one for time.

I thought it was a tremendously good idea. I made a camera, a compass, and a clock that narrated image location and time respectively.

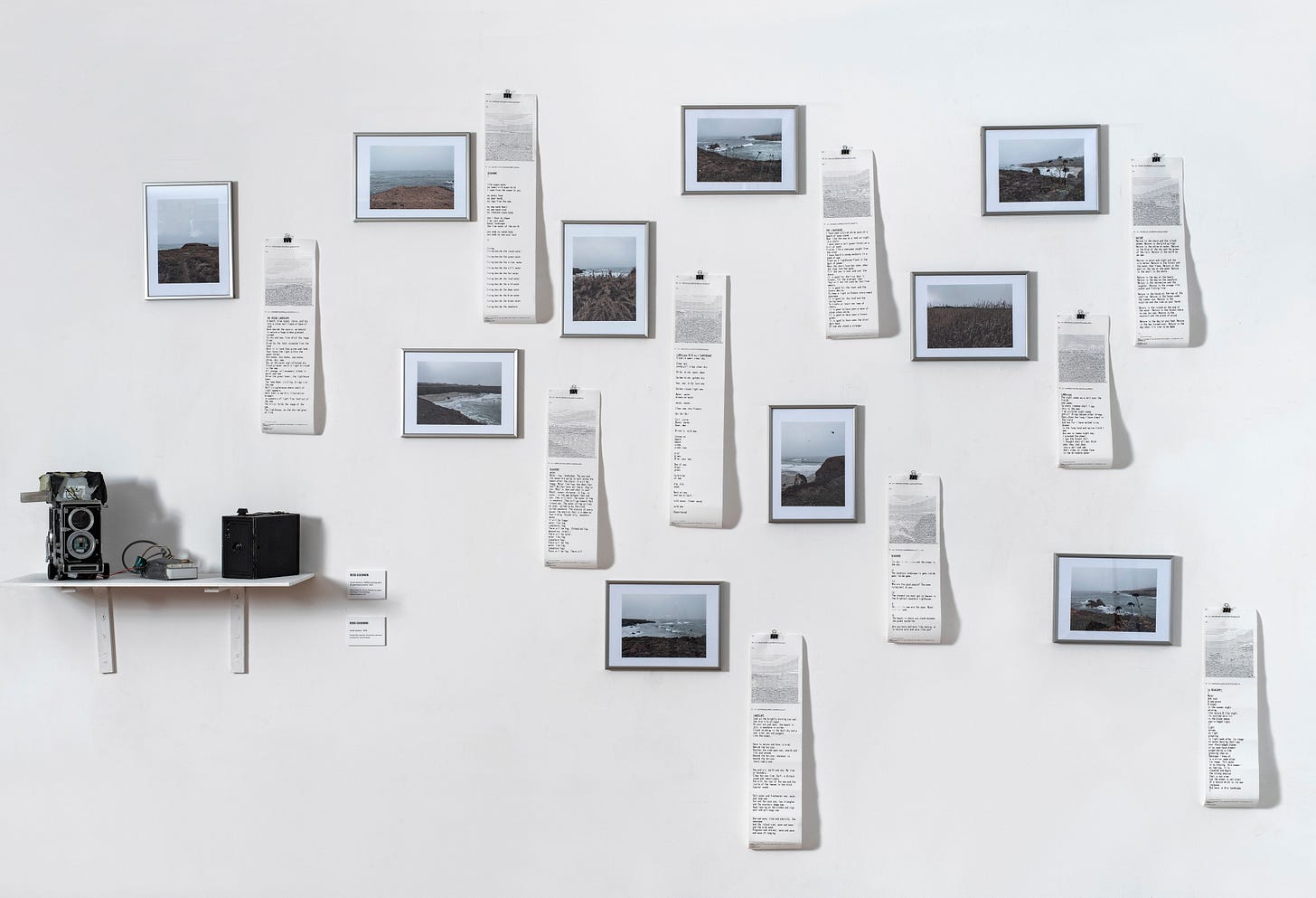

word.camera

But then I had this idea [around] 2015 or 2016 of putting all these components in a car and driving around. You know there's a practice called war driving? It’s where hackers drive around and try to hack into wifi networks. But basically, [with] mobile computing in a car, you can cover much more ground more quickly than on foot. And I just thought it would lend an interesting texture to the resulting text because of the added velocity and the mobility that a car provides. So the initial idea was called word.car. [...] I evolved this idea until in early 2017 [when I pitched this project to] the initial incarnation of Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence program. They were looking for a really simple first project to get the program off the ground. I said, you know, if you can get me a rental car from New York to New Orleans or somewhere like that, [for] the price of a one way rental car, I can deliver this project in about a month.So the turnaround time was very fast. It was really a rapid prototyping exercise. It went from idea to reality in about four weeks. [...] It was quite an experience. The machine wasn't [working] perfectly the whole time by any means. But I think that lends some of the interesting qualities to the text. So I was pretty pleased with how it went in the end.

KA: I love that project. And so the output of this project, of course, is a linear novel.

RG: Yes, that's right. It's the narration of the trip, but it doesn't really relate to the trip anymore. It's almost abstracted out to a level that relates to the places we passed by and the temporal space we inhabited. But it's its own story apart from our experiences in the car.

KA: That's the one that you reprised for Paris recently.

RG: That's right. This year I did a reiteration of the project in Paris where we drove from Versailles to Paris, a much shorter trip, and created a new manuscript with new technology that vastly outstripped the original language models I used for 1 the Road. But the result wasn't that much better, which is very funny in a certain way. The result is constrained by the framework of the project itself, which is that it's this linear narrative that's disjointed because the central thread is the constantly changing location, the constantly changing time, and the constantly changing imagery. [...] There's a lot of similarities between the two manuscripts that I really didn't expect.

word.camera x VERSA photographs, AI-generated poems, 2022, Ross Goodwin . Infinite Object + NFT. Edition 1/1 . 2022 © Photo : Jean-Louis Losi (L’Avant Gallerie Vossen)

KA: Yes, I was going to ask you about that, whether there were appreciable differences in that output.

RG: I think this time it was more poetic just because the language model has gotten better. That said, I had a lot of tricks for training the more primitive versions of these large language models to make them perform well. But I feel like [that’s] been almost lost in the technological advances that have happened in the last few years - [those tricks] are not as necessary. Now you can just train these off the shelf models and they do a good job of generating text in almost any style. But the similarities outstrip the differences between the two experiments. They both had this central thread of the journey.

One of the questions I was trying to answer with the project initially was, what kind of stories are embedded inherently in the journeys we undertake? Is a journey inherently a story, and vice versa? I think that a journey is inherently a story and [that] there is one embedded in every journey, no matter how small or insignificant the journey is.

We're talking about exposition, description, and perhaps dialogue over time, which is the definition of a narrative or a textual narrative. I was interested in exploring the space of automated storytelling in the hope that it could contribute to augmented storytelling in the future. My hope with these projects is not to remove the impetus [from human authors to write] but to suggest other implements, other methodologies, for writing that might not be readily apparent, but [that] might be enabled by these technological advances.

KA: So you've also been working recently with the Allen Ginsberg Foundation.

RG: That's right. And my project is a little late, so might not be much to talk about there, but yeah, go ahead.

KA: Well I was just going to ask you about the project. And you're working with [curatorial platform ] the Verseverse on it.

RG: It’s not really strictly a collaboration, but it's being released through the Verseverse. It’s my project and it's immensely humbling to be asked to do this by the Ginsburg Estate itself. I'm thrilled to be working on this and I hope it has an impact with people who appreciate Ginsburg's work and [who] might be able to appreciate it through a new lens.

[The project] is going to be like a generative overlay on his photographs, describing or riffing on elements in the photos poetically in his voice, spatially overlaid on the photos, if that makes sense.

KA: So you're using Ginsburg's photographs - because he has a whole body of photographs - and [working with] a large language model that you've trained on his writing.

RG: Yeah, that's right.

Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Metropolitan Museum of Art, N.Y.C., 1953 © Allen Ginsberg, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles.

KA: And you're going to produce new works from this.

RG: That’s correct. Each edition of this work will be directly inspired by one of the photos. So it's centered around these photos that I think are tremendously interesting artifacts of his life and his work.

KA: I feel like there's something here that's about exploring or reconfiguring the archive. Are you thinking about the archive here? Because you're obviously working with and drawing new ideas or new combinations and configurations of ideas out of the archive. Is that in your mind as you're working through the project?

RG: That’s always is in my mind because whenever I'm working with a large language model, there's a text corpus or an archive of text that's being invoked and I think [for] large language models - or just language models in general - it's a way to make an archive speak, and that provides [an] interaction with an archive that might not be possible otherwise. Whether it be generating new material in the voice of the archive, or even asking the archive questions and having those questions answered in a relevant way per the information contained within.

KA: There seems to be something apropos about this being Ginsburg. I know that anytime you're working with these methodologies - like you just said - you're always working with a corpus. But is there something about it being Ginsburg in this case?

RG: The history of his work has been in the background the whole time in my mind, because [for example] Open AI labels his work as obscene and [as material that is] unable to be [used as a dataset for training]. Ginsburg encountered tremendous difficulties with his work being labeled as obscene and unpublishable in his lifetime. In fact, that was a major court case with Lawrence Ferlinghetti and that whole group. I think it's interesting that [those issues are] echoed in the ways in which his work can engage with these large language models, and that the entities in control of these language models have criteria [by which] his work is judged to be obscene, when, you know, we've [in the meantime] established as a culture that obscenity in the context of poetry can be acceptable and even somewhat beautiful. It's very interesting to me that this has come full circle in that sense.

KA: And so what's the state of it now?

RG: It’s going to be released in January, I think.

KA: I also wanted to ask you about SUNSPRING. This is going way back.

RG: Seven years ago.

KA: SUNSPRING is a short science fiction film. The script was written by an AI and it starred Thomas Middleditch and was directed by Oscar Sharp. [For context I would say that] most people would recognize Thomas Middleditch as the guy from [HBO Series] Silicon Valley.

Thomas Middleditch in SUNSPRING (still)

RG: Yeah, that's right. But he also does improv Shakespeare and he's a great improv actor. And that lends itself well to this role in this film.

KA: I love this film. It’s one of my favorite things ever. It’s acted beautifully and has these amazing production values and there is a dissonance between that and how the actual script, [being written by AI], is so disjointed and therefore intriguing. Can you describe more about that project or give it more context?

RG: I think that project is still the one that people go back to when they're talking about my work. I'm about to go give a talk about that project in Singapore in about a week, with Oscar. We still get invited to speak about that work because I think it remains relevant, even though the technology is advanced beyond what we had when we made that film.

I think [SUNSPRING] teaches us something about what actors do because of the interpretation that was required in order to make [the script] make sense. Actors do that with any material though - as it turns out language without context doesn't make very much sense. Usually the same sentence can be said in two different contexts and mean dramatically different things. A good actor has a handle on that, how to deliver a line with inflection, movement, et cetera, such that the meaning of the line is apparent to the audience in the way that the director intends it to be. I think that is apparent with SUNSPRING. When you watch it, it's just sort of obvious that's what the actors are doing. And then you ask yourself, well, how is that different from any other film actually? But beyond that, I think it's worth asking - why hasn't anyone repeated the experiment? It's still the only [well-known] film [where] the screenplay is generated by AI. And sure, it could be done again pretty easily. Lots of people have made screenplays that make a lot more sense using AI but I think the thing that's missing is having actors of that caliber who can deliver the lines and make a movie that's that compelling. It doesn't really matter in the end that the screenplay didn't make very much sense. It's the actors who really sell the work. And they really made the whole thing possible.

KA: Was it a similar experiment with [the film you made with] David Hasselhoff?

RG: Yeah, that was sort of a follow up.It's called It’s No Game. And then we did a third one called Zone Out that’s even weirder. But yeah, the David Hasselhoff one was very interesting. That was co-written by Oscar Sharp and the machine, so there were generated segments in there and also human written segments that connected the generated segments. It's No Game was also a great short film. It didn't get as much attention as SUNSPRING, but I think it still got some and that was immensely gratifying.

KA: And everybody likes David Hasselhoff.

RG: Everybody likes David Hasselhoff. He was great to work with.

David Hasselhoff in It’s No Game (still)

KA: So I want to switch directions for a second and just zone out a little bit to general questions about Generative AI, and AI and art practice. I'm really interested in what artists have been making using these tools, but there's also a lot more to say right now about how these technologies will be affecting art and writing in the future. Do you have thoughts about where this is all going in the grand scheme of things?

RG: You know, I don't. I don't presume to know where it's going in the grand scheme of things. But I think that artists are continuing to push the boundaries of this technology and suggest new visions about where it could go. I think that's tremendously important. I think the role of artists and in AI is to elevate the public discourse about the technology. [...] I think people need to understand more about how this technology works. That is not magic, that it's driven by data and it's based on statistics and it's not just a magic bullet for any problem. It really has limitations and affordances based on the means of its inception. It is something that I think is going to continue to evolve. Artists are going to continue to have this role of suggesting different directions that it could go.

KA: When you think about AI and art practice, would you think of it as a tool? A medium? A paradigm?

RG: I think it's all of the above. It can be a tool. It can be a medium. It can be a paradigm. It can be a co-creator. All of these descriptions are sort of like humans grasping at straws for how to describe this new phenomenon, and I think it really points to the limitations of our language and the anthropocentricity of a lot of our language around AI in that we can't really get beyond [the idea] of it just being a human replacement or a human substitute and not something wholly new and in and of itself. I think that could be problematic in the future [...] but I hope we can think beyond the ways in which our vocabulary around these technologies limits us, and reframe the way we view these technologies to expand our imaginations for how they could be used and how they could be interacted with.

KA: The other question that has come up for me is how art and design education should be approaching AI or how AI is going to come into that sphere, how it changes production for emerging artists, and how the institution should be evolving in order to accommodate or facilitate these different production methods. Do you have any thoughts on how educators should be approaching all this?

RG: Yes, I think they should be approaching it as inclusively as possible. I think that a lot of these tools for design and for art making and creativity are going to really hinge on advances in AI and [will] depend on these technologies. So I think that educators who are limiting their students' access to them are limiting the students’ ability to leverage these technologies, and limiting their students’ futures with a lot of these vocations.

For example there are a lot of ways to make a sculpture. You can build it up layer by layer additively, or you can chip away at a block of marble subtractively. There are a lot of ways to achieve the same vision. [It’s the same with] design and creativity, generally speaking, there are always multiple directions [in which] to go. But I do think that AI is going to influence the frontier of what's possible in a huge way in that it's going to allow individual practitioners to accomplish a lot more on their own, and it's going to allow groups to collaborate in different ways that are not possible now, and it's going to allow for new types of design and new visions for design and different applications that we haven't even thought of yet.

So I really think that educators need to include some sort of AI primer in their coursework or, at least suggest to students that these tools are going to be important in the future, because I think that's undoubtedly true.

KA: And then at the same time, at a certain point, the technologies recede. For example 20 years ago, everybody was wanting to talk about - did you use Photoshop or whatever [on that project]? And anybody working with art and technology dreads always being asked about the technology and not the art or the ideas. But do you think this is a similar thing that in, you know, five years, nobody will even make the distinction that something has used AI?

RG: I think it's funny because in the past AI had a moving goalpost problem where it was sort of defined as anything a computer can't do yet. And as those problems were solved it became more of a marketing term, which it really is now for, for a class of technologies that are inspired by the way the human brain works or might work.

But in terms of your question about whether it's going to fade into the background, so to speak, I think time will tell. It's really hard to say what the horizon is on that. But I think that it’s plausible that we could be moving the discussion beyond something like - did this use AI? - to, of course it did and, what's the result, and is the result interesting?

[When] making something with AI that doesn't need to involve AI, you have to ask yourself, what did the AI contribute to the project? Did it make the project achievable faster than it would have been otherwise? Did it get the practitioner to the solution more quickly? Did it allow for an idea to be executed that wouldn't have been executable otherwise? I think we always have to be asking ourselves [questions about] what the AI is contributing to our ideas. There are a lot of projects that are using AI that don't need to be, but that's because it's the hot, sexy technology right now. That's not necessarily a bad thing, but I think as time goes on, projects that [use AI] that don't need to be using AI, will be less emphasized and we're going to be seeing more mainline uses of the technology and more people are going to be continuing to find applications for AI and creativity that are going to be adopted (or not adopted) as time goes on. So, how people are using it in the future, it's really hard to say.

KA: Yeah, impossible. One might say that it's impossible to imagine how that might look. So on the subject of wild speculation, I have been asking people to project forward and make some predictions about - what will the life of an artist, writer, designer look like in 2033? Is there anything that comes to mind when you see the direction of culture or, our artistic era now, where it's going to, where it's evolving?

RG: I think one of the things we can look back to is the invention of the camera, because I think that the emergence of generative AI is very similar to the invention of the camera in the 19th century. Painters were tremendously frightened by the camera when it first emerged. They thought it was going to kill painting and [clearly] it had a different result. [Photography] took something that was once expensive, for example [a] family portrait, only rich people could afford [one]. And then by the late 19th century, almost anyone could afford a brownie camera to take a family portrait with. Producing a photorealistic image went from requiring one measure of human effort to a different measure of human effort.

Photography wasn't even considered an art form for about 100 years. So I think we're traversing a similar trajectory with AI, but you know, it's very much more sped up. So I guess to answer your question, thinking about what a designer's life is like in 2033, maybe look at what a photographer's life was like in 1899 or 1910. How did photography change artmaking in that period? Photographers were largely seen as technicians and not artists initially. So I think there's going to be this hump we have to get past where people who are engaging with technology to a significant extent might be seen as technicians more than artists or creative practitioners. I think we are seeing [this, in that] Generative visual AI and the ways that's perceived by the public as not being art or not being valid art, or being boring or however people are perceiving it negatively. As that becomes more mainstream, and as that becomes more accepted as a practice, we're going to be seeing methodologies emerge that are more accepted as artmaking methodologies and not just as technical methodologies.

KA: So well said. Thank you so much, Ross. It's so interesting to hear your thoughts on this. [Your work] has been really inspirational to me over the years.

RG: It's been a pleasure. And thank you for having me. It's been really wonderful having this conversation.