Thoughts on Immersive Media

Art that got kidnapped and forced to go on the road with the circus, but that came to love its captors

I've been wanting to write about immersive media for a while. On one hand, after more than two decades working in art and technology—producing and presenting media art across a wide range of forms, including whatever we might have called "immersive" before the term started to mean what it means now— I feel deeply familiar with the histories and contexts of immersive media.

On the other hand, immersive media has been having a 5 - 7 year-long Cinderella moment, gaining prominence through the technological advancements and radical reframing done by institutions like TeamLab, Fotografiska, Barbican Immersive — places I hadn’t yet had the chance to experience firsthand. That changed last week, when I finally visited Mercer Labs in New York City.

I need a word to indicate the differences between what is going on at Mercer Labs-type institutions and what came before (or what happens in parallel in different contexts.)

From the 1990s, many artists were shaping the immersive dimensions of new media art. Artists were into embodied interaction, responsive environments, domes, and early VR experiments, that invited viewers to navigate digital space through bodily presence. Immersive media was a space of encounter between body, machine, and environment that was bringing questions about audience, relationality, and technology into new spheres in order to question them. In Canada, this was presented at festivals and in academic settings, people were paid badly, and there were shaker knit sweaters, de-alcoholized tallboys, and governance committees.

But now, should we call it commercial? Retail? For-profit?

For-profit immersion is different because (1) people pay for it (the ticket was $60!) (2) it is specifically designed so that lots of people will like it, and (3) people go to see it. I don’t want to speculate on the causality of this chain.

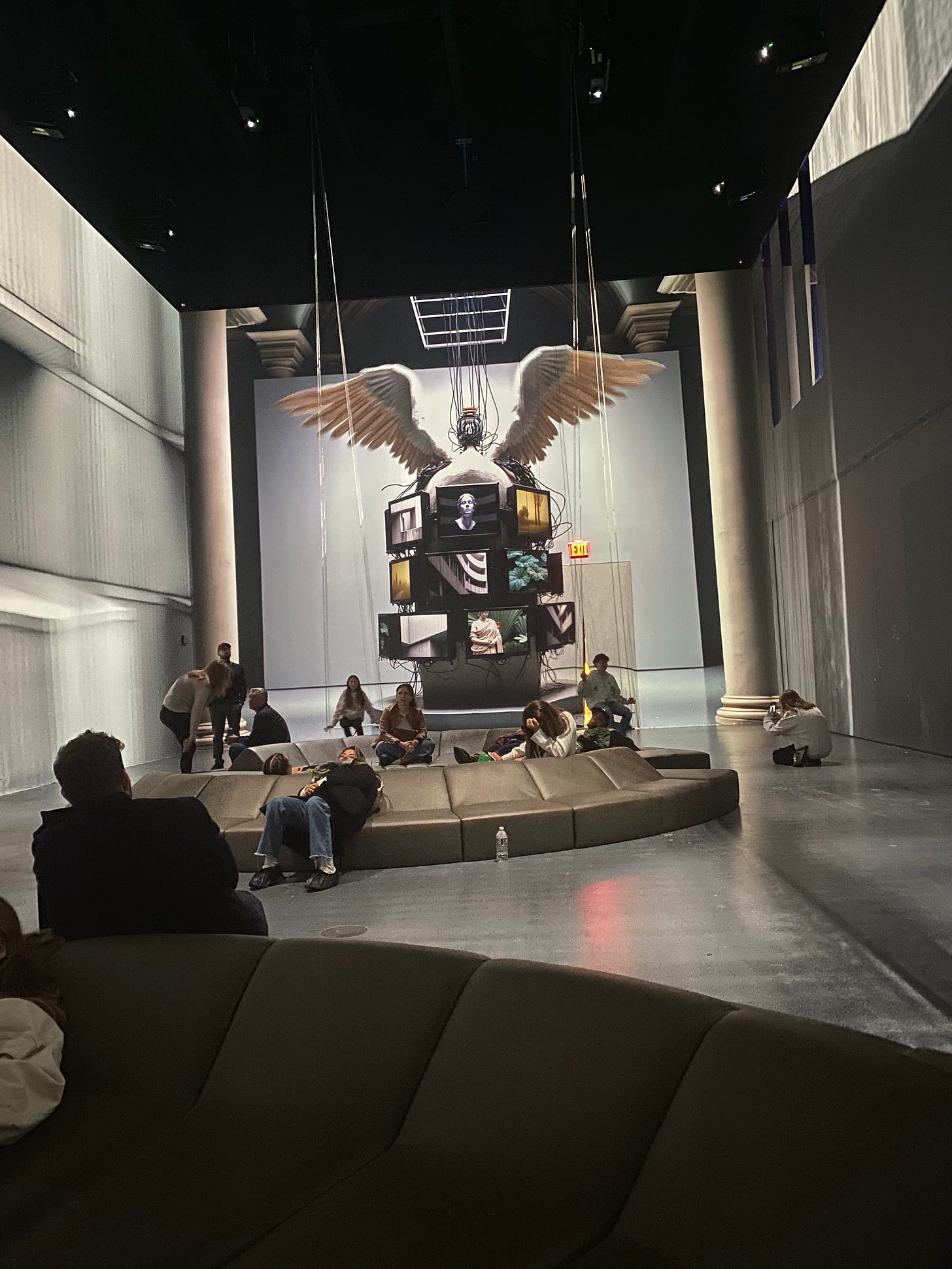

The show at Mercer Labs is called Maestros and the Machines, the artist is Roy Nachum. Picture a black box. There’s a ceiling and a floor, though the floor is treated as a projection surface and you have to wear little booties. The rest of everything else is image.

In totality, things feel large, lush, calm, moving slowly as though you are gliding through a sculpture forest.

There are swings hanging from the ceiling, and long, low couches. Mostly, the furniture enables you to lie around, cultivating a feeling of seamlessness, but other times, the projection pulls back and the lighting forefronts the couches so you feel like you are in a really weird waiting room.

Maestros and the Machines “invites us to reconsider the timeless masterpiece… historical works are no longer revered as static relics but are reimagined as living, evolving frameworks”. So it’s no surprise that we see some of the Greatest Hits: Looming, romanesque figures, Mondrians dissolving cinematically, a version of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus that looks like it’s been done with a Bedazzler. There are also the requisite number of robotic forms, some with breasts thank god, and a number of images where robotic arms are 3D printing the Venus de Milo.

This is, in general very cool. Yes, you have Yayoi Kusama-inflected Infinity Room-style corridors, seemingly endless spaces, 15 different rooms, the semblance of holography, light gone wild. Sensations of depth. Blending between physical and digital aspects. Things that flutter. Things that undulate. Things move because they can. One room features a 3D grid of 507,000 synchronized LED voxels. Roy Nachum is severely fabulous.

Sometimes people criticize this kind of work as being “instagrammy”. It is true that (well-done) photographic representation does manage to successfully package the wonder. In fact it seems that some of the photos capture it almost better than the real experience can. I’m not sure if that makes sense.

Image from Designboom

My image (yah)

In a photo, you can see the person who is being infused with awe, and that gives you a reference point for scale and allows you to imagine the overwhelming feeling of reverence, admiration, and sacrificial fear they are experiencing. But when you are inside the experience, you can’t witness yourself being infused with awe. The thing that you appear before - the thing that is so much larger than yourself - is a world of image. You can tell by the beanbags. You can’t see the “whole thing” even though you are surrounded by it. Ironically, you feel like you can’t get close to it. Totality is fragmented again, like it is in real life. You as a viewer are plopped down into a new universe where all you can do is stand around like a dimwit and expect to experience rapture.

(Sidenote: if you were actually transported to another planet that was, for example, empty but for huge banks of glittering lavender sand, an undulating moss-green sky, and slow-moving, sentient beanbags, how long would it take you to have a thought other than “Woah”. Is that what happened to us as a species during the long period of time before language?)

The beginnings of immersive media had roots in Expanded Cinema, multi-screen installations and panoramic projections by artists like Stan VanDerBeek in the 1960s who were redefining the cinematic frame, enveloping the viewer in sensorial moving images and sound. His Movie-Drome (1963-1965), which he called an “experience machine”, was an immersive theatre made from a grain silo, where people would lie on the floor and watch a panorama of 16mm and 35mm slides. This was about integrating film, video, performance, and environments to create new experiences and new conceptions of media.

Movie Drome, Stan VanDerBeek (1963-1965)

Maybe it doesn’t matter whether these immersive experiences belong on the same continuum or not. Maybe the point is that immersive media wants to give us something, and sometimes it defaults to astonishment, novelty, big boi beauty. The tools and have changed —masking tape, Macromedia Director, and RCA cables have given way to synchronized LED voxels, Unreal Engine, and disposable booties — but we still gather in darkened rooms hoping to be transported, expanded, undone.